The sap of the plant becomes clear only when the roots have revealed their secret. Patrick Chamoiseau. Texaco. 1977

HISTORICAL RESEARCH FOR THE BOOKS

My name is Peter Curtis, formerly Kürti. My family was Jewish and originated in Slovakia. In the year 2006 I completed a reconstruction and history of my family’s past. I then began a fictionalized novel describing my family’s escape from Prague after the Nazi occupation in March 1939: The Dragontail Buttonhole.

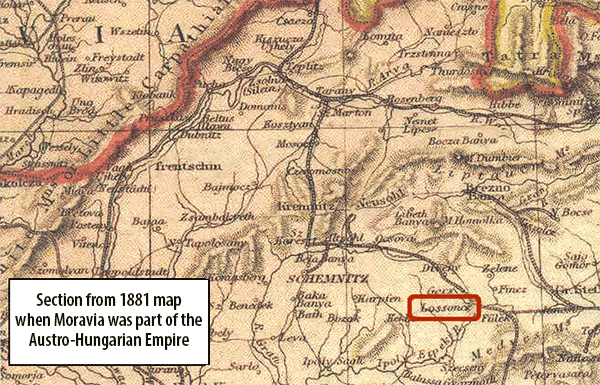

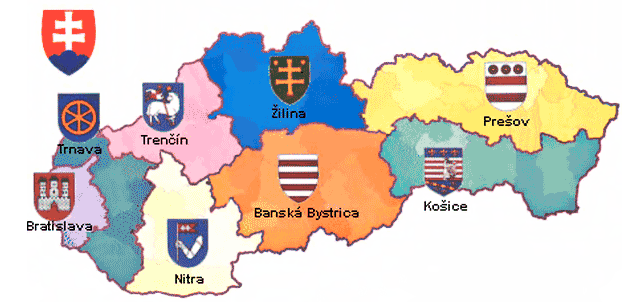

My father’s family came mainly from Central Slovakia, previously part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. My mother and her family, the Grossbergers (or Gadors) and the Schnellers came from Salgótarján, still part of Hungary – about 100 miles from the Kürti home region. From the 1850’s, or possibly earlier, the Kohn or Kürti family and their more distant relatives lived in central Slovakia (Středoslovenský kraj) particularly in the towns of Bela, Zilina, Zvolen, Svaty Martin, Banská Bystrica, Lučenec, Levice and Ružomberok . This mostly mountainous region is sandwiched between Hungary to the south, Poland to the east and north and Germany to the west.

Banská Bystrica, an industrial town (and the administrative capital of the region) where my first recorded ancestor Samuel Kohn grew up, lies at the intersection of 3 mountain ranges, the Nizke Tatry, Veĺká Fatra and Slovenske. Surrounding the town are the foothills of the low Tatras, rich with fruit trees and small farms. This is where German colonists settled in the 13th century to extract silver and copper until the mines played out in the 17th century. The town has a small but handsome late 18th century Baroque center

Derivation of the name: Kürti -- The Kürti or Kurty family was Jewish. A Jew is defined as any person whose mother was a Jew – or anyone who has gone through conversion to the Jewish faith.

Mixture of German and Hungarian town names where the family lived

My family lived in the Košice, Banská, Bystrica regions

Main Square of Banská Bystrica, Slovakia Birthplace of my Great Grandfather, Samu Kohn. 1844

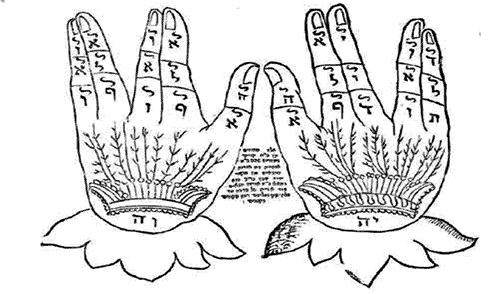

The family’s original last name was Kohn – a name derived from the Israelite priest tribe of Kohanim. Central European Jews were known as Ashkenazi who were descendants of the Jewish tribes that, over the centuries, spread north from Palestine into Eastern Europe. These days the name Kohanim has morphed into Kohn, Cohn, Coen, Cohen, Katz, Khon, or Konh depending on circumstances and need. Kohanim gravestones bear the image of two hands with thumbs touching, fingers spread out in blessing.

The Kohanim are said to be descended from Aaron, a priest and supposedly brother of Moses, who performed certain rites and animal sacrifices at the Great Temple in Jerusalem.

Recent DNA research has shown that in 3 geographically distant countries, about 30% of modern Kohanim have common elements on the Y chromosome indicating a single male ancestor. Others have different male lines that probably descended from other priests.

The first known ancestor on my father’s side, Samuel or Samu Kohn, grew up in a village on the outskirts of Banská Bystrica, southeast Slovakia ( called Besztercebánya when in Hungarian hands) He was Jewish and a peddler by trade. German colonists developed the town in the 13th century and extracted silver and copper from the hills until the seams played out in the 17th Century. Surrounding the attractive baroque town are the foothills of the Tatra Mountains, rich with small farms and orchards.

I discovered that the names of villages and towns in that part of Central Europe changed repeatedly depending on who was currently in charge-—Germans, Hungarians, or Czechs and Slovaks. Jewish families also changed their names to fit ethnic trends; a major strategy to keeping business going in an anti-Semitic environment. In 1905, for example my family name changed from Kohn to Kürti, a Czech name.

Kohanim Blessing (see http://kahan.hubpages.com/more-on-the-Kohanim-DNA-question)

As I slowly approached retirement, and stimulated by seeing several films about WW2 in the 1990’s (such as Schindler’s List, Sunshine and The Pianist), I began to sift through inherited photographs and materials, arranging for translations of Hungarian and Czech letters and documents. I also started to read more history of WW2.

My family (except for my mother) rarely mentioned the past. After WW2, they probably thought that it was best not to regale a child with the horrors of loss and refugee-hood. As I have read in memoirs about the Holocaust, there was probably also a sense of shame in surviving in the war while so many others disappeared.

From the age of 18 onwards, I was caught up in the grind of medical studies and the excitement of professional life – and later immersed in marriage, personal and family interests. I never thought to ask more than superficial questions – what a pity.

I want my novels to show how individual lives and history intertwine, and how fate can be decided for us by courage, foresight, other people, accidents, chance, initiative and by the very small decisions of each day. In certain circumstances, turning left or right at the door might spell life or death!

The Countries of the Dragontail Buttonhole

HUNGARY

The Austro-Hungarian Empire began in the 17th Century under the Hapsburgs, later known as the dual monarchy (Austria and Hungary had separate governments within the Empire - formed in1867 after the Austro-Prussian war). From early on within this Empire, the aristocracy, as in other parts of Europe and England, generally disdained commercial enterprises, owning vast tracts of land and serfs. They retained the power to control and run their country, and were content to allow others, especially Jews, develop the commercial aspects (industry, banking, insurance) of the economy.

1867-1918 was the golden era of Magyar-Jewish relations. The Jews were given the opportunity to build the business and banking infrastructure of Hungary, activities, which the Magyar elite still disdained. Although there was economic collaboration between ethnic and social classes, there was always clear social segregation between them. The Magyar elite and Jewish business people did not even frequent the same hotels, cafes, resorts and restaurants and there were strict limits on club memberships and access to university education.

The Kürti, Feiner (Fodor) and Waldmann families (all Slovaks) were located in Slovakia, mainly in the towns of Lučenec, Banská Bystrica, Levice, Svaty Martin and Ružomberok where a mixture of Germans, Gypsies, Hungarians, Slovaks and Ruthenes lived. The Gadors (Hungarians), lived first Salgótarján in Northern Hungary and then in Lučenec.

WW1 came about partly as a result of the increasing desires of various cultural and Slavic groups to re-assert their languages and culture and break from the longstanding and rigid Austro-Hungarian Empire. Emil Kürti and Zoltan Gador (my paternal and maternal grandfathers) both had fought with the Austro-Hungarian troops in WW1 against the French, British and American forces, and it was commonplace for up to 5 languages /ethnic groups to be represented in regiments. After the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was extinguished and the size and boundaries of other central European countries changed dramatically. Two brand new countries were created out of the old Empire – Czechoslovakia, where our family lived – and Yugoslavia.

The Trianon Treaty at the end of WW1 (1918) forced Hungary to give 63% of its citizens and 13% of its lands to the surrounding countries of Poland, Rumania and the newly formed Czechoslovakia (made up of Slovakia, Bohemia, Moravia, Ruthenia and part of Silesia). As a result of these land changes, large numbers of ethnic Hungarians ended up living in other countries. Immediately after the war, the Hungarian Karolyi regime abdicated and the Soviets (this was also the time of the Soviet Revolution (1917)) sent in Bela Kun to set up a communist regime and take control of the country.

Béla Kun was the Bolshevik son of a middle class Jewish family who lived in Russia during the revolution. Lenin funded him to return to Hungary and start a pro-soviet newspaper, for which he was imprisoned for a time. Kun’s regime was known as the Red Terror by its ruthless suppression of opposing groups and peasants, and Kun subsequently organized attacks on Slovakia and Rumania in an attempt to gain back the lost lands. Béla Grossberger/Gador, my mother’s uncle, an avid communist, became Kun’s right hand man in 1918. When the Kun regime eventually failed. Uncle Bela went into hiding for many months, even faking insanity to stay out of the way of vengeful fascists. He ultimately escaped to Western Europe and then to Australia.

After its defeat in WW1, Hungary’s desperation to regain its previous lands and glory persisted. The reward of acquiring previously lost territories was used by Hitler to recruit Hungary into the Axis Power group at the start of WW2. In the 1930’s, racists in Germany began to blame the Jews for causing Germany’s humiliating defeat in WW1 and the severe economic depression in Europe that followed the war.

Hitler became the German Fűhrer in 1933, after which Jewish stores in Germany were boycotted, and Jews were dismissed from state positions. In September 1935, the Nuremburg laws carefully defined who was a Jew, thus preparing the way for specific attacks on the Jewish people, culture and economic integrity. In 1938, all the Jewish temples in Germany were burned, and the cemeteries razed in 1940. The nationalistic and fascist activity going on in nearby Germany and the post- WW1 dispossession of Hungary with its severely damaged economy and lacerated pride led leader Admiral Horthy to latch on to the coat-tails of the expansionist German policies.

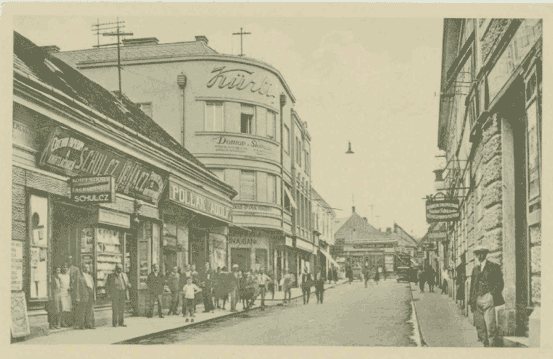

The Town of Levice. My Great Uncle Gideon Kürti’s store. Date ? circa 1928. This was a few years after the creation of Czechoslovakia where the government and population were working hard to create a new cultural identity

In the 10th Century the Slovaks united with other tribes (Czechs and Poles) to form the Greater Moravian Empire. The region was then invaded by the Magyars who drove out the lowland Slavs. In medieval times (1100 AD), a variety of ethnic groups migrated into Slovakia and were absorbed into the Kingdom of Hungary.

Further north and west, the Czechs formed their own Kingdom which was most powerful in the 14th century under Charles the Fourth who was also the King of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Emperor. Many Germans, Belgians, and Dutch were invited to settle on lands decimated by the Black Death. Other refugees were escaping religious persecution in France, Italy and Switzerland. In 1600, a large group of Croatians arrived, fleeing political unrest. Many Italian and French Artisans who were hired to carve marble and stone, and make stained glass windows for the great castles, churches and monasteries of Central Europe also settled in Slovakia.

In general, the Slovak region was ruled harshly by the Hungarian Kingdom preventing social and economic development. The Slovak serfs worked in the forests and as work gangs on the Hungarian plains. The Slovak language, although of Slav origin, is somewhat different to Czech and is based on the Kralická Bible text brought to the region in the 17th century by the Moravian Brethren escaping from Catholic persecution. Thus, Slovak became known as the “Language of the Bible”.

The Czechs and Slovaks were steadily Germanized and Catholicized under the auspices and laws of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and many Germans were sent to be settlers throughout the empire. However, in 1836, Magyarization of central Europe was aggressively implemented by the Budapest Hungarian Diet (one part of the Hapsburg Empire) requiring all business and cultural activities be undertaken in Hungarian. Even the Slovak churches were required to pray and preach in Hungarian. The idea was to unify the Empire as uniformly Hungarian. Of course, the ethnic groups preferred to keep their cultures and relative autonomy.

This forced the Slovaks into uniting behind a written language based on the central Slovak dialect, though it marginalized them from participating fully in the regional economy, preventing industrialization and the growth of a middle class.

In the 1840’s a nationalistic revival took place in Czech and Hungarian lands with a revolution of Czechs and Slovaks led by Josef Kossuth against the Austro-Hungarian regime. This was initially very successful, and the Emperor finally had to ask the Russian Czar for military assistance to put it down. Kossuth remains the national Slovak hero to this day.

In 1849, in keeping with the social reforms of the Empire, (five years after my ancestor Samuel Kohn’s estimated birth), the Austro-Hungarian Empire lifted its discriminatory restrictions, and all ethnic groups, as well as Jews, were permitted freedom to travel and access to all areas of economic life. This was a time of a great revival for Czech culture, with freedom of the press, political activity and considerable prosperity. The Emancipation Act acknowledged that Jews were full legal citizens and could own land and property. This gave the small town Jews great opportunities. They were able to change from living as peddlers (my great grandfather Samuel Kohn) and small traders to starting their own businesses and buying property at a time of the rapid industrialization of the country.

Eventually in 1863, the Slovak Matica (Foundation) was formed as the first phase of a transition to a Slovak government – and was approved by the Hapsburg Emperor at Turciancsky Svaty Martin (where my grandmother’s family lived. Her father owned a hotel and stables). After 1865, the German influence became more dominant in Slovakia, and in 1875 the Slovak Matica was dissolved.

Jews in Czechoslovakia

Documentation shows that Ashkenazi Jews were living in Prague in 908, and by 1700, the city was the center of one of the largest Jewish communities in the world. This was the result of the attraction of a tolerant society and persecution in other parts of central Europe where they had been ejected from towns and cities. In 1620, the Hapsburgs defeated the Czechs and annexed their lands, and thus Hungary, Slovakia and the Czechs were joined with Austria for the next 300 years.

In 1726, the “Familiant” laws were enacted to try to control the growth of the Jewish population – they tended to have many more children than the Slovaks. These laws restricted the number of families permitted to live in villages and towns, and allowed only the eldest son in a family to marry. In fact there was a Jewish “body tax” — an official residence permitting not more than two adults in a dwelling, so the children often had to move away. Although secret marriages took place (so called “attic marriages”) in general, the younger children were often sent to Hungary or Poland where such laws did not exist. Jews were also restricted to Ghettos, which retained the unsanitary and decrepit conditions of mediaeval times.

Between 1867 and 1918, Jews were faced with the dilemma of either integration with Slovaks or Hungarians, or remaining within their own orthodox culture. At the same time, the three dominant ethnic groups (Czechs, Hungarians, and Germans) were struggling for ascendancy in Slovak society. Jews tended to adhere to the high prestige languages (German or Hungarian), but were particularly attached to German culture which offered wonderful music, burgeoning science, philosophy, literature and a broader, world view of society. The process of integration of Jews into Slovak or Hungarian society was also accompanied by the steady attrition of religious traditions and understanding of Hebrew - which, however, regained some strength after WW1, when many traditionally oriented Hasidic Jews migrated from Eastern Europe to Slovakia.

In 1918 when the Czechoslovak republic was formed, the newly constituted Jewish national council declared its loyalty to the new government and asked for full civic and legal rights, cultural autonomy in Jewish education and the unimpaired use of Hebrew. However there were conflicts between assimilationists and extreme orthodox groups (as now in Israel). This newfound optimism was dampened by anti-Semitic riots in Moravia, Prague and Slovakia. These died out as the leaders of the country Eduard Beneš and Tomáš Masaryk demonstrated their democratic enlightenment.

The Zionist movement (which promoted a new Jewish homeland in Palestine) came to Slovakia in the 1890’s and there were active local groups in the towns where our family lived or worked. The Zionist organization raised funds to support emigration and settlement in Palestine. Our family particularly helped finance the startup of a Czechoslovak Kibbutz (eventually named after the great Czech president Jan Masaryk) and paid for orange trees to be planted there. In the 1920’s Jewish prosperity in Slovakia led to the construction of new synagogues in Lučenec (1925), Košice (1927) and Žilina (1932). However, in 1932 the world economic depression struck, and a number of Jewish families left Czechoslovakia for Palestine (the Eretz Israel movement).

In WW1, Hungary and Czecho-Slovakia were exploited for their mineral, oil and industrial resources as well as for soldiers (My grandfather, Emil Kürti fought on the Polish front, and Zoltan Gador, my mother’s father was in Poland with a Hungarian military engineering unit). After WW1, on October 19th 1918, the new independent combined Czechoslovakia was created (though it contained 4 million ethnic Germans in Bohemia – also known as Sudetenland). These events were strongly influenced politically and financially by the expatriate Slovaks living in the USA who exerted much pressure on the US Government. At the Trianon Peace treaty Britain and France guaranteed the frontiers of Czechoslovakia –essentially this meant that they would come to its aid if its integrity was threatened.

For Czechoslovakia, 1920 to 1936 was a time of increasing prosperity, democracy and cultural development. …when the Kürti family business (importing and representing luxury English fabric/textile companies) expanded to meet the clothing and tailoring needs of a growing middle class that was taking up the styles and fashions of Western countries

In 1930 there were 356,000 Jews in the whole country (2.4% of the population). At that time, about 40% of the capital invested in Czech industry was Jewish owned, mainly in mining, steel and private banking. The economic slump of 1929 caused many Jews to emigrate to the west.

Anti-Semitism was still rampant and was on the platform of many right wing groups, the Vlajka (flag) group, the National Union and the Hlinka Guard (Slovak People’s Party). The German speaking bulge of Czechoslovakia that bordered Austria and Germany, the Sudetenland, had long been a center of anti-Semitic hatred and was naturally allied to Germany and Austria. The powerful political leader of that region was Konrad Henlein. On the other side of the coin, “genuine” Czechs in the rest of the country would not forgive the Jews their long time adherence to the German language and culture and support of German political parties. Thus the Jews were accused of infamy by both sides as well as committing the additional sin of being communists. And to make matters worse, the communists also accused the Jews of being conservative reactionaries.